Recent Posts

Categories

- Articles (19)

- Interviews (9)

- News (68)

- Reviews (5)

Archives

- October 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (1)

- April 2016 (2)

- March 2016 (2)

- February 2016 (3)

- October 2015 (3)

- September 2015 (5)

- August 2015 (7)

- July 2015 (9)

- June 2015 (10)

- May 2015 (10)

- April 2015 (11)

- March 2015 (6)

- September 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- March 2014 (1)

- June 2013 (2)

- May 2013 (3)

- April 2013 (3)

- March 2013 (3)

- February 2013 (1)

- December 2012 (3)

- November 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (6)

- September 2012 (5)

- August 2012 (1)

- June 2012 (1)

- May 2012 (3)

- April 2012 (1)

- March 2012 (4)

- February 2012 (2)

- January 2012 (3)

- November 2011 (2)

- October 2011 (4)

- September 2011 (2)

- August 2011 (4)

- July 2011 (1)

- June 2011 (2)

- May 2011 (1)

Tags

action adventure Anna Susanne books Bristol british horror Business Bear Carnival of Sorrows Christmas comedy comic comics competition Contest Faith Healers fantasy Feature Friday fiction film making flash fiction Follow Friday Gabriel Cushing hellbound media Horror humour indie film Kickstarter Mark Adams Matt Warner Nikki Foxrobot podcast Poetry publishing romance scary sci-fi short story supernatural The Flesh Angel thriller vampire web series writing zombies zombie vampiresSubscribe to Blog via Email

- state a characters feelings

- describe upcoming events before they happen

- use verbs and adverbs in your dialogue tags or actions that explain the emotion behind what was said or done.

- reflect deeply on events that have just happened

- and just generally state the obvious

- You run the risk of insulting the reader’s intelligence. If a character thumps their fist on a bar the reader does not need you to tell them that the character is angry.

- Explanatory interior monologues can start to make character’s seem stupid, naïve, neurotic or simply unbelievable.

- If you start explaining yourself the reader will start to notice you explaining yourself, and if they notice you then they aren’t immersed in the story.

- Darren Robbie (aka “Chopsy”) – key animator and commercials director with Aardman Animations

- Sarah Cox – who collaborated on several films using archive material for the new MShed Museum in Bristol

- Neil Whitman – freelance animator and graphic designer with the BBC

- Nick Murray Willis – prolific indie animator and winner of 2010’s DepicT competition

A Great Escape shout out to Desert Bus for Hope

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 19th November 2011

Great Escape founders Chrissey and Rich have long been fans of Canadian comedy troop LoadingReadyRun and they are a huge inspiration for us.

Great Escape founders Chrissey and Rich have long been fans of Canadian comedy troop LoadingReadyRun and they are a huge inspiration for us.

Every year for the last four years they have organised what has become the internet’s biggest live fund raising event; Desert Bus for Hope.

The team play the worst video game ever to be nearly released. Desert Bus is a mini game on the never released Penn & Teller Smoke and Mirrors for the Sega CD. The player drives a bus from Tuscon, Arizona to Las Vegas across the intervening featureless desert in real time. The trip takes eight hours after which you get one point, turn round and start the return journey. The road is straight, but the bus lists to the right and if you don’t play constantly you crash and have to start again.

The team play continuously for as long as their supporters pay them to and currently the time for Desert Bus 5 is 113 hours. Last year the team bused for over six days.

The whole marathon is broadcast over the internet and while the bus rolls along the highway the group take on challenges, run auctions and competitions and interview special guests for donations.

All of the donations go to Child’s Play, a charity dedicated to providing games and toys to children in hospitals all over the world, who otherwise don’t get the chance to play like normal children.

It’s a wonderful cause and an addictive, entertaining event that is hard to turn away from. Go watch, get addicted and get involved! Send them your challenges, bid on the auctions and give whatever you can for the children and to keep the bus on the road.

After Desert Bus 4, the team made a music video based on the game called Tuscon or Bust:

Tagged as: causes, charity, Child's Play, comedy, Desert Bus, Desert Bus for Hope, events, games, LoadingReadyRun, marathon, news

Categories: Blog, News

Leave a comment

Chrissey’s Writing Tips #3

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 26th October 2011

Every writer wants people to read their story. My next few articles deal with the how to engage readers and keep them reading. This month I’m starting at the beginning.

GOING FISHING – hooking readers with the opening of your story

If you want to keep the pages turning then the first thing you need to do is make sure the reader turns the first page. My personal rule when looking at the opening of a story is this:

The first paragraph must make them read the first page.

The first page must make them read the first chapter.

And the first chapter must make them keep reading.

STARTING A STORY

So what makes a good opening?

Avoid thinking you need to sum up the story so far to bring people up to speed before you start telling the story you want to tell. In other words, think long and hard about where your story actually starts and start from there.

Going back to Writing Tips #2 about showing and telling, I personally feel that you must open with a scene. You have a whole story in which to incorporate the back story and character history; your reader does not need to know all of it up front.

Now a scene doesn’t have to mean dialogue or action but a line of either of these is often a good way to open, especially for people starting out in writing. Another option is description. A characterful piece of narrative summary can work in the hands of someone experienced.

You are not committed to keeping the first thing you put down on paper. Try a few different things out. People take time to warm up when they start writing, so the first thing you write is very rarely the best thing.

OPTIONS FOR OPENING LINES

Action

Action creates motion and direction of some kind which in turn creates anticipation. Whether it’s running (to where, why?) or sitting (for how long, are they waiting for something?), the very act of performing an action creates curiosity in the reader.

Jean Auel Clan of the Cave Bear

This line sets the scene and introduces the character in one, very efficient sentence. Not only can you picture her, immediately as a reader you want to know why she is naked, is she in danger, why is she running?

Dialogue

It’s very hard to get an opening line wrong when you start with dialogue; although it may not be the strongest or most original way to open, it is always at least moderately effective. All dialogue anticipates a response and the reader will want to know what the response is.

Enid Blyton Five on a Treasure Island

Description

You can also start with description, by setting the scene, but make sure what you’re describing is interesting. Usually it’s best to avoid the weather. Weather is everywhere; show us something we can’t get by looking out the window.

Statements and questions

If you’re not going to use action, dialogue or description to open your story make sure you make it characterful. Make a statement out of the blue or ask a question. Say something outlandish or outrageous.

Breaking the rules

No one ever said you can’t break the rules. Anything goes so long as you remember always your aim: make the reader curious. So you can start with telling us about the weather:

Terry Pratchett & Neil Gaiman Good Omens

But be aware, if you do this the reason people will read on is that they assume you are making some kind of joke or at least a point. In the case of Pratchett and Gaiman the first paragraph continues:

All of the examples in today’s post were taken from books on my bookshelf. Do you have some good examples of opening lines to share? What’s your approach to starting a story?

Tagged as: advice, beginning, opening, opening hook, starting, writing, writing advice, writing tips

Categories: Articles, Blog

6 Comments

Christmas Writing Competition 2011

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 24th October 2011

That’s right, it’s competition time!

That’s right, it’s competition time!

Write a 1500 word Christmas themed short story and you could win £10 of Amazon gift vouchers and publication on the site.

Take a look at our competitions page for all the details and instructions on how to enter.

Good luck writers!

And remember, if you’re interested in getting involved with the site, contact us by email or through Twitter or Facebook.

Tagged as: Christmas, competition, Contest, free submission, holidays, prizes, writing, writing competition

Categories: Blog, News

2 Comments

Terror of The Killer Carnivorous Coat: Coming Halloween 2011!

Posted by Rich - 20th October 2011

Exciting news here at Great Escape Towers, as we’ve just released the trailer for our upcoming half-hour Halloween special: Terror Of The Killer Carnivorous Coat.

Check it out!

Tagged as: comedy, david curtis, evil, Fabric, fear, funny, Gabriel Cushing, Halloween, Horrible, Horror, humour, nathan head, Not just a COAT, scary, Silly, Spooky, supernatural, Teaser Trailer, Trailer, Ugly

Categories: Blog, News

4 Comments

Marley Hamilton interviewed by BCfm

Posted by Rich - 9th October 2011

Actor, writer and all-around ace person Marley Hamilton has recently done a radio interview with BCfm (Bristol Community Radio).

In it, she discusses her acting career, namedropping Hollywood directors, gallivanting around the world and, more importantly, upcoming Great Escape web-series Gabriel Cushing Versus The Zombie Vampires and short film Pancakes With Steve, which we are co-producing.

Listen to it below!

BCfm – Interview with Marley Hamilton – 07/10/2011 by thegreatesc.com

Tagged as: acting, acting school, bcfm, Bristol, bristol community radio, bristol films, chat, CineMe, dancing for architecture, discussion, film production, filmmaking, Gabriel Cushing, giggly, indie filmmaking, interview, local, los angeles, Marley Hamilton, martin scorsese, Pancakes With Steve, point zero productions, radio interview, spoken word, Tobacco Factory, uncertain proof, upcoming films, writing

Categories: Blog, Interviews, News

1 Comment

Chrissey’s Writing Tips #2

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 26th September 2011

Last time I looked at the stylistic choices of tense and perspective. Once you’ve decided on these basics, the next job is to get the events of the story down on the page. Now the subject starts to get really complicated, so I’m going to start with the biggest and most important point.

GETTING THE POINT ACROSS – Showing and Telling

There are many books on the craft of writing, but almost all of them will, at some point, talk about the subject of showing vs telling. Showing the important parts of your story rather than telling them is at the core of successful, immersive writing. So, let’s take a look at the fundamentals.

SCENES VS NARRATIVE SUMMARY

One of the hardest things in writing is getting the balance right between simply telling your reader what happens (narrative summary) and showing them the events as they happen (scene).

Narrative summary has its place, but one place it certainly does not belong is your opening paragraph. Always try to open with a scene to ensure you hook your reader and draw them into the story. I’m going to do an article on openings at a later date.

Narrative summary can be used to quickly convey unimportant details, perhaps to show time passing or cover an incidental piece of action that, while not important to the plot, is important to the flow of the story telling. To cut a long story short, everything that is important to the story should be shown through scenes.

Here’s a quick example of the difference:

Narrative summary:

Marie walked into the bar and confronted Jason about his affair. He tried to explain but she would have none of it.

Scene:

Marie stormed into the bar. “Who is she? Some tramp from work or what?”

Jason took one look at her flushed cheeks and burning eyes and shrank back.

“No it’s not like that, there’s no‒”

“Don’t lie to me, I saw the texts. I saw you with her the other night.”

“Look, whatever you think you saw you’re wrong, she’s just a friend.”

Marie thumped her fist on the bar. “I know what I saw!”

She spun on her heel and marched towards the door. Jason scrambled round the bar and took off after her.

The second version is longer, granted, but it is more visual and more engaging for the reader. We get a wealth more information from seeing their conversation than we do being told about it. Narrative summary is often utilitarian and cold. By showing the action in a scene, you can convey emotion and expresses the tension between the characters in a way that inspires the reader to care about what happens next.

A useful exercise is to read through a piece of writing, either your own or someone else’s for comparison, and try to identify what is shown as scenes, what is told as narrative summary, and what the balance is between the two.

YOU DON’T NEED TO EXPLAIN YOURSELF

On a smaller scale, showing and telling can be equated to demonstrating and explaining. In a good piece of writing, you hope that your demonstration is so good that you don’t need to explain it at all.

You explain yourself when you do the following:

Time for another example. Let’s go back to Marie and Jason in the bar again, extend it out a little and see how each of those numbered points above looks in context:

Version A:

“Stay there, I’m coming over,” Marie said over the phone then hung up.

Jason was worried. (1) She had sounded very upset on the phone and he wondered if she suspected something (4). If she confronted him about it he would just tell her the truth; that Zoe was a friend and needed his help. (2)

Some ten minutes later Marie stormed into the bar. “Who is she? Some tramp from work or what?” she accused. (3)

Jason took one look at her flushed cheeks and burning eyes and shrank back. She was angry and she knew something, but what? (5)

“No it’s not like that, there’s no‒”

“Don’t lie to me, I saw the texts. I saw you with her the other night,” she interrupted (3)

“Look, whatever you think you saw you’re wrong, she’s just a friend,” he replied (3)

Marie thumped her fist on the bar, angrily (3). “I know what I saw!”

She spun on her heel and marched towards the door. Jason panicked that he wouldn’t see her again if he let her leave, (1) so he scrambled round the bar and took off after her.

“Marie, wait. Listen to me. Her name’s Zoe, and she really is just a friend. She’s been having some trouble with this guy and she needed some help, that’s all.”

In many cases the best thing to do with all that explanation is just cut it out. Highlight, delete, sorted. But, if you think that leaves things a little too vague or lacking in detail, you might want to convey your point another way, for example by adding in a little bit of body language or less direct interior monologue. Sometimes simply rewording a line can help.

Version B:

“Stay there, I’m coming over,” Marie said over the phone then hung up.

Jason worried at his thumb nail, considering what she might have seen or heard. It played on his mind for some ten minutes until Marie stormed into the bar.

“Who is she? Some tramp from work or what?”

Jason took one look at her flushed cheeks and burning eyes and shrank back.

“No it’s not like that, there’s no‒”

“Don’t lie to me, I saw the texts. I saw you with her the other night.”

“Look, whatever you think you saw you’re wrong, she’s just a friend.”

Marie thumped her fist on the bar. “I know what I saw!”

She spun on her heel and marched towards the door. Jason’s heart leapt into his throat and he scrambled round the bar and took off after her.

“Marie, wait. Listen to me. Her name’s Zoe, and she really is just a friend. She’s been having some trouble with this guy and she needed some help, that’s all.”

But what’s wrong with explaining? Doesn’t that make sure the reader understands what I am trying to say? Consider you are watching a movie and during the middle of an intense action scene the directors voice is suddenly heard explaining the character’s thoughts and emotions. Wouldn’t that completely throw you out of the experience? Well it’s the same with writing.

There are a number of drawbacks to over explaining yourself:

Ultimately, it all comes back to the first and most important point – the writer should be invisible; they should act only as an invisible bridge between the reader and the story. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but those thousand words can paint many pictures if used well.

Your feedback is most welcome. Let me know if you find these articles helpful, if you’ve got any of your own advice to add, or if you have a suggestion for a future topic.

Tagged as: advice, beginner, creative writing, fiction, immersive writing, scenes vs narrative summary, showing vs telling, writing, writing advice, writing fiction, writing technique, writing tips

Categories: Articles, Blog

4 Comments

An Evening at CineMe

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 14th September 2011

Rich and I had the pleasure of attending an animation showcase hosted by Bristol based group CineMe yesterday evening. Marley Hamilton, one of the stars of our upcoming web series, joined us for the event at Bristol’s Tobacco Factory theatre and bar.

James Ewen and his colleagues at CineMe had compiled a two hour showcase of short animated films of outstanding quality, including pieces by:

The Great Escape will be showing some of our films at one of CineMe’s upcoming showcase events, so stay tuned for a chance to see some of our work on the big screen.

In the meantime, do check out CineMe’s other upcoming events, including an editing workshop with Bafta Award winning editor, Don Fairservice, which some of The Great Escape crew will be attending. They will be launching their new website at the end of the month, where you can find lots of exciting independent videos to watch.

A big thank you to CineMe for an enjoyable evening.

Tagged as: Aardman animation, animation, Bristol, cinema, CineMe, Don Fairservice, event, indie film, networking, news, Sarah Cox, showcase, Tobacco Factory

Categories: Blog, News

2 Comments

Meet the people behind the site

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 31st August 2011

This week we’ve got a special blog post for you, a chance to meet the people behind the site and see a bit of what we do.

Film

Fiction

The fiction side of the site is run by Chrissey Harrison. She is an aspiring author who has recently had her first (hopefully of many) piece accepted for publication, and also a bit of a science geek.

Although the internet is full of writing communities, there is always room for more. We’re hoping to bring more writers to the site and establish this as a place of collaboration, encouragement and skill sharing for new writers.

Comics

Mark Adams (soon to be Dr Adams, we kid you not) runs the comics portion of the site, bringing together a variety of artists and writers. Mark is a student of cult film and television with an almost unhealthy obsession with horror and Dr Who.

One of our strongest links is to Hellbound Media, a new, up and coming comic publisher who you will find doing the rounds at the conventions. Also making regular appearances is FinalBeyond. We hope to establish a community of comic writers and artists and encourage collaboration and sharing.

Multi-media or trans-media storytelling is something we feel very passionate about and are looking to delve deeper into. This means in the future you can expect to see themes and characters occurring across all three mediums on the site and potentially even breaking into other mediums such as games and radio-plays from time to time.

If you’d like to get involved in any aspect of the site, be it film making, writing or comic artistry, join our forum or get in touch via email, Twitter or Facebook, we can’t wait to meet you.

Categories: Blog, Interviews, News

Leave a comment

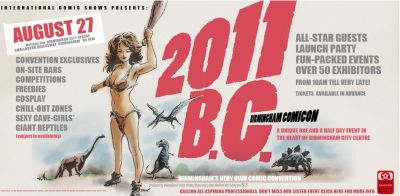

Hellbound Media at Birmingham Comicon

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 27th August 2011

If you’re off to Comicon in Birmingham today then make sure you check out Hellbound Media, The Great Escape’s favourite comic writing geniuses!

If you want a taste of what you can expect you can read two of their short comics right here:

And, while you’re there, say hi to Mark Adams, writer, director and general magic maker for many of the films on the site.

Tagged as: birmingam, comicon, comics, convention, hellbound media, meetup, news

Categories: Blog, News

Leave a comment

Chrissey’s Writing Tips #1

Posted by Chrissey Harrison - 21st August 2011

Writing is one of those things that is easy to learn but difficult to master. I by no means claim to be an expert, but I have picked up a few of the basics, which I would like to pass on to you.

Perhaps the most important thing I have learned is that I have a lot to learn. If you start writing thinking you know everything, or that your way of doing things is unique and superior to everyone else’s method, you will not get very far. So, tip #1 is to open yourself up to the resources out there and learn.

Author David Kazzie provides an amusing look at the realities of being a writer. Of course, I like to think that aspiring writers like the character in the video don’t really exist; we’re smarter than that. Hopefully you won’t see yourself in this… So You Want to Write a Novel

On a more serious note, you can find recommendations for resources on The Great Escape forum. Please add your own resources and help us compile a useful directory.

I’ve pulled together a few of the things I’ve picked up, including, tenses, perspective, showing vs telling, pace and editing which I’ll be posting over the next few months. This week I’m looking at goals and basic stylistic choices.

THE HOLY GRAIL – What you are really trying to achieve

Image source - Early British Kingdoms

What is your ultimate goal as a writer? Is it to tell a story? Is it to entertain your reader? Is it to create a complex, believable plot and rich, multi-dimensional characters? It’s all of these things, but the real challenge is to do all of this while remaining invisible; to immerse your reader so completely that the story becomes real for them.

Any time a plot point seems unbelievable, or the reader has cause to question the author’s choice of words, or the author inserts some reference to themselves, then the reader is dumped out of the narrative. This is what you don’t want.

Do not assume that you’re going to achieve it all the time; even bestselling, published authors have a few moments in their stories where this happens. But, the more you can minimise the slip ups, the better your writing will become, so always keep this goal in mind.

STORY TELLING CHOICES – Tense and Perspective

Tense and perspective are choices you make, usually up front, although if you change your mind later it’s not the end of the world; you can edit to change it.

TENSE

When telling someone a story, as in literally talking to them about something that happened, you would almost always use past tense. Why should a written story be any different?

As with everything in writing, your task as a writer is to immerse the reader and make them forget that they are reading at all.

When you write in past tense you ask them to imagine that the events took place at a specific time, in a specific place. This is an easy thing for them to believe, so they accept it and get on with absorbing the characters, settings and events.

When you tell a story in present tense you are asking them to believe that the story is taking place at that moment. This is less easy to believe, and, however unconsciously, some part of the reader is thinking, “this is impossible.”

This is not to say that you should never write in present tense. Sometimes it can be very effective, but, as a beginner new to writing, past tense is both easier to write and more natural for both writer and reader.

Once you have chosen a tense, you must be consistent with that tense. You shouldn’t need to use more than one tense in a story, let alone a paragraph or sentence. Of course I refer to the three major tenses here (past, present and future). Grammatically there are tenses within tenses, known as aspects:

From The Oxford A-Z of Grammar & Punctuation

| Simple | Continuous | Perfect | Perfect continuous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past | I walked | I was walking | I had walked | I had been walking |

| Present | I walk | I am walking | I have walked | I have been walking |

| Future | I shall/will walk | I shall/will be walking | I shall/will have walked | I shall/will have been walking |

Read more on Wikipedia – Gramatical Aspect

Whilst you should stick to one consistent tense, you can use the varied aspects of that tense to create the effect you want and give a sense of time and order to your writing. The exception is dialogue which should use whichever tense is appropriate to give an accurate representation of the character’s words as they were or are spoken at the time the events took or take place.

PERSPECTIVE

In literary terms, you have three choices of perspective – first person (I walked), second person (you walked) and third person (he/she/they walked). Choosing a grammatical perspective is not just about the way you construct your sentences, it also determines how your reader connects to your characters and experiences your story.

Ignore second person perspective; it is rarely used and even more rarely published. For the same reason that present tense makes it harder for your reader to become immersed, directing the story at “you” when it is blatantly not you, makes for an awkward, unnatural reading experience.

Image source - mysterious-strange-weird.com

First and third person perspectives are equally valid choices and both have their benefits. First person naturally allows for a more intimate point of view, but it constrains what you can describe to what that character experiences; some writers find this tricky.

Third person perspective should not be thought of as one perspective at all. It is a spectrum, running from intimate to distant. At one end you have an intimate third person perspective, told strictly from one character’s point of view, and differentiated from first person perspective only by the language. At the other end of the spectrum is something called omniscient perspective.

Omniscient perspective allows the writer to see and experience all, jumping from character to character as needed. For some writers this is what they naturally gravitate towards. It is not wrong, but it is old fashioned. By its very nature it distances the reader from the characters and emotions in the scene.

There are then many shades in between. Developing your grasp of perspective is something that comes with practice. The perspective you choose will also need to fit your genre. For an emotional story, for example a romance, something towards the more restricted, intimate end of the spectrum will likely give your readers a better experience. Meanwhile, a broad, sweeping, historical epic may benefit from a more detached style.

I hope you’ve found this post helpful. Next time I’m going to take a look at the bane of existence for all authors; showing versus telling, and a little about non-verbal thesauri – showing emotions visually. I’d value your comments and any suggestions for future posts.

Tagged as: advice, creative writing, novelist, perspective, tense, tips, writer, writing, writing advice, writing tips

Categories: Articles, Blog

1 Comment

Books | Submissions | Hall Of Awesome | Mailing List | About us | Cookies Policy | Contact us | RSS (Atom) |